Research in the decision-making processes of substance abuse

By Jennifer T. Allen

JOSH BECKMANN’S INTEREST IN PHILOSOPHY steered him through the related fields of epistemology, phenomenology, and the philosophy of science until he began questioning how you can blend these ideas with actual data. That question led him to get a second bachelor’s degree in psychology.

After earning his master’s and doctoral degrees from Southern Illinois University, Beckmann came to the University of Kentucky in 2008 as a post-doctoral student working in Michael Bardo’s and Greg Gerhardt’s labs. In 2014, he joined the Department of Psychology as an assistant professor with a focus on choice behavior.

Beckmann and his team of graduate students concentrate on the decision-making processes in models of substance abuse. “We are trying to understand why an organism would choose a drug of abuse over having a concurrent option to partake in some other reinforcing behavior such as eating food,” Beckmann explained.

Trying to figure out what it is about drugs of abuse and how they compete with other reinforcers to create a sort of myopic drug-related behavior that is characteristic of abuse is at the core of Beckmann’s research. And they are looking at it on multiple levels.

Inside the Lab

The research begins by measuring behavior. In one scenario, they do this by asking a rat if it wants to take cocaine or eat a sugary sweet pellet. Then, they create different conditions where the rat may move toward one direction or another. Even though the environment and conditions are the same, some rats go for the cocaine and some go for the pellet.

“The idea is to understand the neurobehavioral processes that govern the behavior,” Beckmann said. “We are trying to understand what it is about the rats that don’t go for the cocaine. What kind of neurobehavioral processes are underlying those drug-related decisions?”

Beckmann is also conducting similar research on obesity, which has added complexity. Being obese comes with a great deal of changes in metabolism, so it is difficult to separate the metabolic effect of obesity versus the reinforcing effects that are associated with it, Beckmann explained. To address this, the models isolate certain reward areas in the brain and ask the animal how much they want to stimulate that area. “By doing so, we are trying to find out if we can separate out the metabolic effects that are associated with obesity versus reward changes associated with obesity,” Beckmann said.

Another focus of Beckmann’s lab is gambling behavior and how environmental stimuli will promote a sense of suboptimal choice behavior. This is done by giving a rat two options: the first gives them food 50% of the time and the second only 12.5% of the time. If signaled in a predictive way, such as with lights or sound, a subjective experience is created making the 12.5% more prominent, and then it becomes the preferred option. “They choose the 12.5% option with a signal, even though they can get more reward by choosing the 50% option,” Beckmann said.

Graduate students have been integral to the success of the lab. “Without much staff in the lab, anything that is going to get done is student dependent,” he said. “That goes from designing and running the experiments to analyzing the data and programming the computers. Students are involved in pretty much every single aspect of the research.”

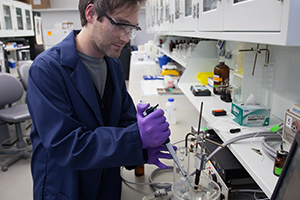

Josh Lavy, lab manager builds an electrode for neural recordings.

Seth Batten, 3rd year behavioral neuroscience and psychopharmacology doctoral student in psychology, calibrates a recording electrode.

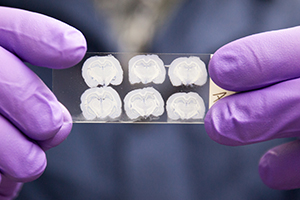

Slide-mounted coronal slices of a rat brain.

What does studying choice behavior tell us?

“If you want to study the rewarding benefits of a drug, you only study the drug. If you want to study the rewarding effects of food, you only study food. If you want to think about people with substance abuse disorders, they have concurrent reinforcers all the time,” Beckmann said.

Choice behavior research looks at what an individual does when offered multiple choices. “If we know what is controlling the behavior, it allows us to better intervene for therapy,” Beckmann said.

Next steps for Beckmann’s lab include applying for grants to further the research. Beckmann is currently writing a grant with colleagues in the Department of Behavioral Science focused on finding the basic mechanisms that are constant across species (rats and humans) so they can translate what they find effective in people into the rats to further study the underlying neurobiological processes. “This will hopefully help us delve deeper and find some neural targets that may lead to a better therapeutic solution down the line,” Beckmann said.

Funding a Lab

When Beckmann joined the College of Arts & Sciences three years ago, the College and Department of Psychology provided start-up funds to get his lab off the ground. He was also able to bring a small amount of funding from a post-doctoral National Institute of Health (NIH) training grant, which transitioned into a small amount of start-up funding once Beckmann came on as faculty.

“In this day and age, grant money is really hard to come by,” he said. “The success rate of getting a Research Project Grant (RO1) from the NIH is really low and it doesn’t appear to be going up. If you want to start a new lab, it is pretty much dependent on start-up funds".

” Without funds to begin research in a new lab, there is little hope for landing a grant. “The start-up funds allowed us to expand quickly and get to the point of being ready to apply for new grants,” Beckmann said. “If we didn’t have that money, we would be dead in the water until the next grant came by.”

As Beckmann thinks of the future, he is focused on one goal.

“I hope to get to a place of knowing how we better treat people with drug abuse issues,” he said.

Josh Beckmann's lab works to uncover the decision-making processes underlying substance abuse.

Pictured left to right: Aaron Smith, 4th year doctoral student; Seth Batten, 3rd year doctoral student; Josh Lavy, lab manager; Jonathan Chow, 4th year doctoral student; and Beckmann, professor in the Department of Psychology

For more information about how to help UK close the gap between bench research & solutions to the most pressing health challenges of our day, contact Laura Sutton at (859) 257-3551 or lsutton@uky.edu.